Products Category

- FM Transmitter

- 0-50w 50w-1000w 2kw-10kw 10kw+

- TV Transmitter

- 0-50w 50-1kw 2kw-10kw

- FM Antenna

- TV Antenna

- Antenna Accessory

- Cable Connector Power Splitter Dummy Load

- RF Transistor

- Power Supply

- Audio Equipments

- DTV Front End Equipment

- Link System

- STL system Microwave Link system

- FM Radio

- Power Meter

- Other Products

- Special for Coronavirus

Products Tags

Fmuser Sites

- es.fmuser.net

- it.fmuser.net

- fr.fmuser.net

- de.fmuser.net

- af.fmuser.net ->Afrikaans

- sq.fmuser.net ->Albanian

- ar.fmuser.net ->Arabic

- hy.fmuser.net ->Armenian

- az.fmuser.net ->Azerbaijani

- eu.fmuser.net ->Basque

- be.fmuser.net ->Belarusian

- bg.fmuser.net ->Bulgarian

- ca.fmuser.net ->Catalan

- zh-CN.fmuser.net ->Chinese (Simplified)

- zh-TW.fmuser.net ->Chinese (Traditional)

- hr.fmuser.net ->Croatian

- cs.fmuser.net ->Czech

- da.fmuser.net ->Danish

- nl.fmuser.net ->Dutch

- et.fmuser.net ->Estonian

- tl.fmuser.net ->Filipino

- fi.fmuser.net ->Finnish

- fr.fmuser.net ->French

- gl.fmuser.net ->Galician

- ka.fmuser.net ->Georgian

- de.fmuser.net ->German

- el.fmuser.net ->Greek

- ht.fmuser.net ->Haitian Creole

- iw.fmuser.net ->Hebrew

- hi.fmuser.net ->Hindi

- hu.fmuser.net ->Hungarian

- is.fmuser.net ->Icelandic

- id.fmuser.net ->Indonesian

- ga.fmuser.net ->Irish

- it.fmuser.net ->Italian

- ja.fmuser.net ->Japanese

- ko.fmuser.net ->Korean

- lv.fmuser.net ->Latvian

- lt.fmuser.net ->Lithuanian

- mk.fmuser.net ->Macedonian

- ms.fmuser.net ->Malay

- mt.fmuser.net ->Maltese

- no.fmuser.net ->Norwegian

- fa.fmuser.net ->Persian

- pl.fmuser.net ->Polish

- pt.fmuser.net ->Portuguese

- ro.fmuser.net ->Romanian

- ru.fmuser.net ->Russian

- sr.fmuser.net ->Serbian

- sk.fmuser.net ->Slovak

- sl.fmuser.net ->Slovenian

- es.fmuser.net ->Spanish

- sw.fmuser.net ->Swahili

- sv.fmuser.net ->Swedish

- th.fmuser.net ->Thai

- tr.fmuser.net ->Turkish

- uk.fmuser.net ->Ukrainian

- ur.fmuser.net ->Urdu

- vi.fmuser.net ->Vietnamese

- cy.fmuser.net ->Welsh

- yi.fmuser.net ->Yiddish

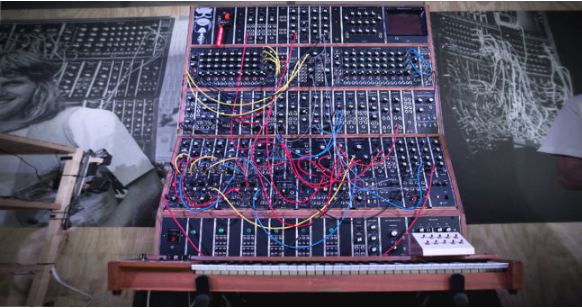

Re-creating a Legend: The Keith Emerson Moog Modular System

Date:2020/2/10 21:18:20 Hits:

Technology changes instruments. Instruments change music. Music changes culture. In 1932, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) became the first museum in the world to document this relationship by starting a collection of these culture-shifting instruments. They also began to demonstrate these instruments in small concerts held in their famous Sculpture Garden.

In 1968, Bob Moog’s synthesizer and musician Walter Carlos had the world rocking to “Switched-On Bach.” MoMA sensed a seismic cultural shift and asked Bob Moog to bring his instruments to the Sculpture Garden for an August concert.

Up to that point, Moog’s company had recognized the potential of a live performance synthesizer but had not finished a production prototype. Now they had an excuse. The day before the event, Bob finished four prototypes: one for percussion, one for lead lines, one for bass — and a primitive chordal synth. Each of the prototypes was fitted with a preset box, which allowed performers to activate six basic sounds at the push of a button. These sounds could be tweaked and adjusted ahead of time.

The night of the concert, more than 4,000 people squeezed into MoMA’s Sculpture Garden to witness the performance. Some even climbed trees and scaled the sculptures to get a better view. The concert was a huge success. The next day, critics heaped praise on the MoMA event for launching the synth as a performance instrument, making Moog a household name and “making music modern.”

Meanwhile, in England, the success of the Moog synthesizer inspired a young musician named Keith Emerson. He hastily sent a letter to Moog, asking for a synth of his own — he even offered to be a product spokesman if they would just send him one.

Keith received a very kind letter from Moog’s East Coast salesman Walter Sear. In the letter, Walter explained that the Beatles and the Rolling Stones had already bought studio synths of their own. He then offered that if Keith was willing to buy one, Moog would be happy to oblige.

Keith quickly paid the money, and a short time later a crate arrived at his door. Inside, Keith found the original 1CA lead synth from the famous Jazz in the Garden performance. What followed was an explosion of prog rock wizardry. From 1971 through 1974, Emerson, Lake & Palmer dropped five major albums – Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Tarkus, Pictures at an Exhibition, Trilogy, and Brain Salad Surgery.

With each album, Keith introduced new synth sounds — sounds that ELP fans wanted to hear live. The problem was, these fans also wanted to hear their favorites from the previous albums. Creating the patches to duplicate those sounds was a tedious process. Keith couldn’t stop the concert between songs to reconfigure his synth for the next song. So the Moog techs simply added new modules to make each sound possible.

In time, Keith’s Moog grew into a 400-pound colossus. It held a pair of sequencers, extra oscillators, filters, amplifiers, contour generators, and low-frequency oscillators. Keith even added several dummy panels to fill the blank spaces in the cabinet and add to the instrument’s imposing presence.

Life was good for Keith and his monster modular synth — and then the ’80s hit. Technology had discovered the drum machine. Music and culture moved on. The synth went from center stage to the bottom of the dance card. For almost a decade, the amazing instrument was neglected, nearly forgotten.

All that changed in 1991 when ELP got back together and planned the Black Moon tour to promote their new album. ELP’s synth tech, Will Alexander, asked engineer Gene Stopp to help get the Emerson Moog Modular up and running. It wasn’t going to be an easy job.

“The Moog was in very poor condition when we first got hold of it,” Gene remembers. “Although a partial repair got us through the Japanese tour, a much more thorough restoration was necessary to make Black Moon and In The Hot Seat possible.”

Engineer Gene Stopp was given the job of bringing the Emerson Moog Modular back to life.

Gene would become intimately familiar with the Emerson Moog Modular, coaxing it through the tour with skill, know-how, and a little bit of luck. But he had other commitments. After a couple of weeks, he withdrew from the roadie game to raise a family.

Fast forward 20 years. Gene is enjoying his “normal” career as a successful engineer. He becomes friends with Brian Kehew, a music business mover and shaker and one-time archives historian for the Bob Moog Foundation — we can all see where this is going. One day, Brian casually mentioned to Gene that the Emerson Moog Modular was in need of repair again. He then casually asked if Gene would be interested in repairing it. Gene called his bluff and said, “Sure, but I’m a family man. Can I work on it in my garage?”

Gene and Brian Kehew (right) saved the Emerson Moog Modular.

Brian and Gene soon found themselves in a rental truck on their way to Marc Bonilla’s studio. Marc was the vocalist/guitarist for the Keith Emerson Band and designated “Keeper of the Emerson Moog Modular.” The synth was back in Gene’s garage by December of 2011.

It didn’t take long for Gene to realize that this project was far more important than just repairing an instrument. “We began to realise that Keith’s synth is like a Stradivarius of the modern era,” he said. “It needs to be preserved for posterity. If you want to replace Keith’s synth, you can’t.”

For example, the original Emerson Moog Modular held seven modules that contained presets dialed in by Keith Emerson himself. By the time the synth arrived in Gene’s garage, there were only five.

Gene immediately realized that he was working on the only Emerson Moog Modular on the planet – spare parts were virtually nonexistent. “You can’t even replace bits of it,” explained Gene. “I tried to buy some spare modules, but they simply didn’t come up for sale, which meant that there were going to be huge problems in the future if any of the original units were to become irreparable.”

Gene’s concerns led to a conversation with Brian Kehew and Mike Adams, CEO of Moog. They discussed the reality of reproducing modules from Moog catalogues from the ’60s and ’70s along with the custom modules from Keith’s synth. At that time, Moog was getting ready to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first Moog synthesizer. The answer was obvious. Moog would re-create Keith Emerson’s synth — down to the last detail.

To make sure that the finished synth sounded identical to its famous predecessor, it would be completely handbuilt from the ground up. Layout films, service manuals, even pages of hand-scribbled notes were dug up and organized. Brian and Gene put together a plan and got to work.

The first real hurdle came as a complete surprise. Up to this point, every electronic component had worked flawlessly when tested on a 921B oscillator. The problems were aesthetic. When compared to the original front panels, the new panels were too black, too shiny, and had a purple tinge. After much trial and error, the problem was resolved and all the modules were ready to be produced.

As a bonus, Gene and Brian added a few modern touches without sacrificing authenticity. Keith’s original synth included a switch that disconnected two of the three 1CA oscillators from the keyboard to create a drone. But this restricted Keith to playing from a single oscillator. Gene and Brian added a switch to turn on two dedicated oscillators, a filter, an LFO, and some other modules to create the drone without shutting down the main oscillators.

They also updated the power supply to be stable, regardless of the load that was placed on it. Finally, they added test points behind the panels that had originally been false panels on Keith’s synthesizer.

When the dust settled, a perfect clone of Keith Emerson’s Moog Modular stood ready to play. And how does it perform? “Squirrely,” laughs Gene. “But that’s only compared to today’s modern synths — and you want it that way.”

“You have to realise that customisation lies at the heart of Keith’s synth,” Gene explained. “If you were able to track down all of the modules that appear to exist within it and then set up the patches that he appears to use, you’ll find that very different sounds emerge.”

Because it was built using only ’60s-era technology and techniques, the Emerson Moog Modular doesn’t ring out with crystal-clear digital perfection. Subtle distortions and noise of every kind assault every note, and that is the secret of the clone’s success.

Now that you know what it took to make the Emerson Moog Modular, what does it take to make it your own? Just give Moog about $150,000 and three months, and Gene will hand-assemble one for you. In no time at all, you’ll be playing “Karn Evil 9” the only way it was meant to be played — on Keith Emerson’s Moog Modular, the one synth to rule them all.

Leave a message

Message List

Comments Loading...